Roots

Wealth is a common factor for the female artist, as well as environment. Historically, the female artist has struggled with overcoming these barriers - those not fortunate enough to be born into well to-do households would find themselves contorted and forcibly molded into societies roles for them.

For Lois Mailou Jones, this couldn't be any more true. Her father was one of the first Black lawyers, her mother a cosmotologist. Together, they lived in Martha's vineyard, her daily interactions with creatives like sculptor Meta Warrick Fuller, and her parents encouragement for Jones to watercolor paint molding her greatly. Art education was only the next logical step, with Jones attending the School of the Musuem of Fine Arts in Boston, even attending Harvard for painting. It was here, however, that she found her calling : the Masks.

The masks, as they were, were simply the cultural depicitions of masks, and their significance. Her fascination with these masks kicked off her dive into her culture - who she was as a person, and what it meant to be a black artist. Les Fetiches, in 1938, is but one expression of her talent. Les Fetiches single handledly changed how the french viewed "Negritude", from a literary work to visual.

Yet, how was she viewed in America? France, being the melting pot of ideas and art for centuries before it, was moderately progressive for its time. America, however, would provide to be more resistant. Jones would often have to send a white friend to pick up her awards in fear that they would be rescinded due to her race. The concept of race in America is one rife with pain, with sadness, and tribulation. Prophet, a sculptor at this time, would find herself unable to find work due to her skin color, respect only earned in France.

Nancy Elizabeth Prophet would grow to become a famous sculptor in her own right, but not without trials and tribulations. Born in 1890, she grew into an era that would see the Great War of World War One rise and fall, in its wake the ashes of a world gone mad.

Originally a design student, Prophet found some degree of enjoyment from painting classes - enough so that when she graduated, she became a protrait artist. However, the seams that barely held the racial rifts together in America were coming undone. Segregation was enforced in larger amounts. There were areas that Prophet herself could not go do due to her skin color; specific water fountains were off limits, movie theaters had times where she could only view films, and the art world as a whole refused to exhibit her due to the fear of offending their wealthy patrons.

The irony in this situation is that Prophet was mixed race; her parents were not pure African America and held native american blood. Her desire to identify as this did little to help her situation. In one unconfirmed case, Prophet told a reporter that she had been accepted into an exhibit, only to learn that the one condition was for her to not show up at the viewing. She rescinded her work immediately.

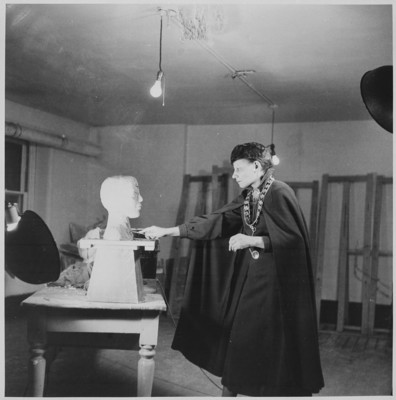

Prophet's struggles did not end there. Like many artists of the past 100 years, Paris was the destination to go, and so Prophet went. With little in the way of money or fame, Prophet created works embodying the persistent and unwavering hope she felt in her work. In 1931, she sculpted Congolais, one in a series of wood busts. At this point, she was nearly starving to death, unable to afford both her craft and food.

Her hard work would eventually garner her a semblence of fame in the art world, but never riches. In many ways, Prophet never sought riches - she only wanted recognition and acceptance.